Table of Contents

Definition of Res Ipsa Loquitur

Res Ipsa Loquitur, which is a Latin term meaning “the thing speaks for itself,” is a legal doctrine that allows a plaintiff to allege negligence when the specific cause of an injury is not known, but the circumstances suggest that the injury would not have occurred absent negligence. In other words, the legal doctrine of res ipsa loquitur allows a court to infer negligence solely based upon the nature of an injury. By invoking res ipsa loquitur, the burden of proof shifts to the defendant, who must then present evidence to rebut the presumption of negligence.

The Elements of a Medical Negligence Claim

In a vast majority of negligence claims, a plaintiff has to prove four elements: duty, breach of duty, causation, and damages.

Duty

Duty refers to the legal obligation of healthcare professionals to provide care to their patients that is reasonable based on current medical knowledge and available resources. A duty to provide reasonable medical care is generally not established until a physician-patient relationship is formed. The typical legal language used in describing a physician’s duty to a patient is that a physician must act as a reasonably competent physician would act under the same or similar circumstances. Expert witnesses generally establish the physician’s duty and the “standard of care” for that duty via expert testimony.

Breach of Duty

Once a duty to provide care is established, a breach of duty occurs when the medical care provided falls below what is considered “reasonable.” To establish a breach of duty, medical experts who specialize in the same field as the defendant (or who are familiar with the issues in the case) are called upon to provide their opinion on whether or not there was a deviation from accepted medical practice. A physician’s duty is not “perfect” care nor is it “excellent” care. The standard for medical practice is reasonable care under the circumstances.

Causation

Even if a physician breaches a duty of medical care to a patient, to be successful in a medical malpractice lawsuit, the patient must prove that there is a link between the healthcare provider’s negligence and the harm or injury suffered. For example, it would be simple to prove that amputating the wrong extremity caused a patient damages. However, it would be difficult to prove that negligence during a cataract surgery caused a patient to have a heart attack since the two events are likely unrelated. Similar to proving duty and breach of duty, plaintiffs must present expert testimony to explain how any alleged negligence by a medical provider led to the patient’s injuries.

Damages

Damages refer to the harm or injury suffered by the patient as a result of a healthcare provider’s alleged negligence. Injuries can be “economic,” which relate to monetary expenses for things such as continued medical care, rehabilitation, and future financial losses or they can be “non-economic” (sometimes called “pain and suffering”) which relate to non-monetary issues such as pain, emotional distress, and loss of enjoyment of life. Successful medical malpractice actions must demonstrate that a patient suffered compensable injuries and that those injuries were caused by a health care provider’s negligent actions.

The Elements for a Res Ipsa Loquitur Claim

By alleging res ipsa loquitur, a plaintiff does not have to prove duty or breach of duty. Applying the evidentiary rule of res ipsa loquitur, if a plaintiff is unable to show direct evidence of a defendant’s negligence, the plaintiff can introduce circumstantial evidence to demonstrate these two elements of negligence. The plaintiff would then have to prove causation and damages for a successful claim. Allegations involving res ipsa loquitur can only be applied in very narrow circumstances under which the following criteria have been met:

- The type of injury suffered must be such that it would not normally occur unless negligence was present

- The defendant must have had exclusive control over the condition that caused the injury

- The injured party must not have contributed to the alleged injury through any voluntary actions

Application and Significance of Res Ipsa Loquitur in Court Cases

In legal terms, res ipsa loquitur creates a “rebuttable presumption” for a claim of negligence, meaning that the burden of proof shifts to the defendant who then must provide evidence to disprove the plaintiff’s theory of negligence. In other words, res ipsa loquitur allows a court to infer negligence based solely upon the circumstances of the incident.

Expert testimony plays an important role in providing insight and analysis into the many complex issues in a medical malpractice case. Because a res ipsa loquitur claim allows a court infer negligence, plaintiff expert witness testimony may not be required if the circumstantial evidence of negligence is strong enough to support an inference of negligence and to show how that inferred negligence caused a patient injuries. While expert testimony may not be required to establish negligence under res ipsa loquitur, expert testimony may bolster a plaintiff’s argument that negligence occurred and may also be required to show how the presumed negligence caused a patient’s injury.

Res Ipsa Loquitur Examples

Suppose that a patient is taken to surgery for an open appendectomy. When the patient wakes up from surgery, he can’t move his right arm. No etiology for the patient’s paralysis can initially be found. In this case, it may be difficult to prove what caused the patient’s injury, so a typical medical malpractice action may have difficulty proving the element of “causation.” However, the patient would likely be able to show that the injury at issue – paralysis of an arm during surgery – would not occur in the absence of negligence. The patient would also be able to show that the anesthesiologist had exclusive control over the situation that caused the injury since the patient was unconscious during surgery. Finally, the patient would be able to show that he could not have contributed to his injury, again since he was under general anesthesia when the injury occurred. Therefore, if the patient hired a law firm to file a health care liability claim, one of the allegations would likely involve res ipsa loquitur.

During litigation, the defendant physician might be able to overcome this rebuttable presumption of negligence by demonstrating, for example, by introducing video evidence that he provided proper care throughout surgery, or that the patient suffered a stroke during surgery that was unrelated to the medical care provided, or even that the patient’s Facebook page showed videos of his arm paralysis prior to his surgery.

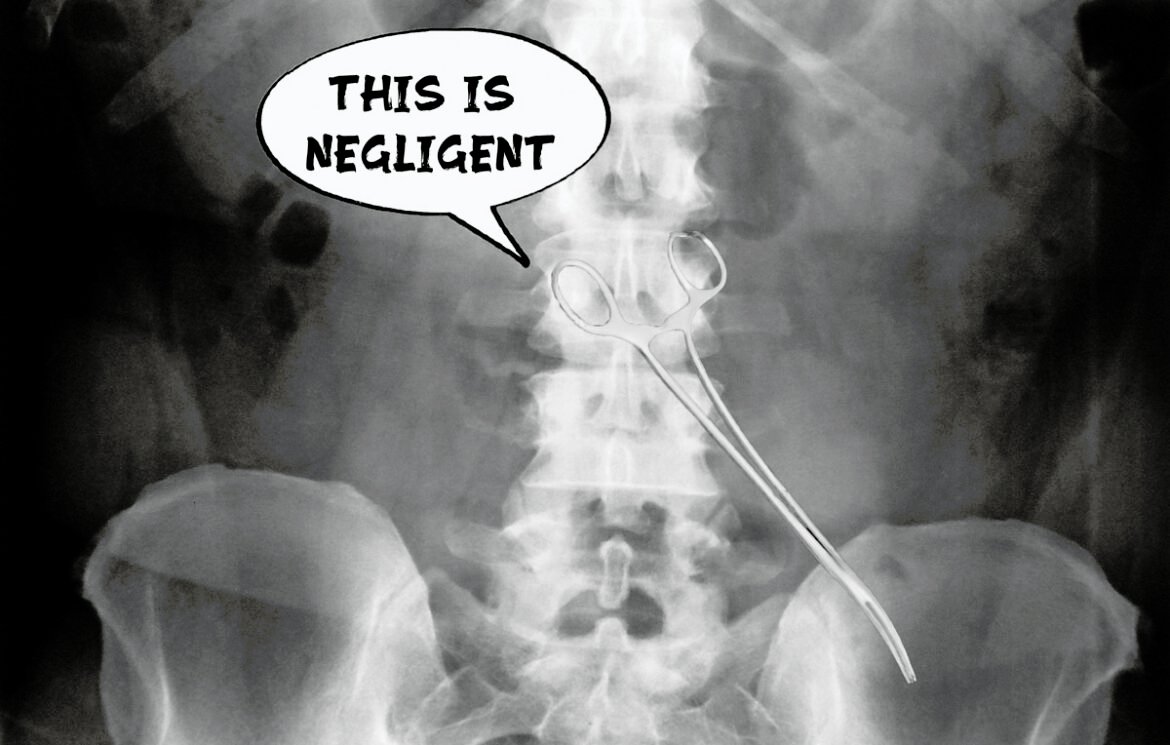

Now suppose that the same patient developed abdominal pain six months after surgery. After going to the emergency department, he is found to have a bowel obstruction. A CT scan of his abdomen reveals that there is a surgical clamp in his abdominal cavity. The situation would also likely meet the criteria for a res ipsa loquitur claim – surgical instruments inside a patient’s abdominal cavity tend not to occur in the absence of negligence, the surgeon had sole control over the conditions, and the patient couldn’t have contributed to his injuries since he was under general anesthesia. The surgeon could rebut the res ipsa loquitur claim by showing that a midlevel provider closed the patient’s surgical incision and the surgeon was not in the operating room when the surgical incision was closed – showing that the surgeon did not have exclusive control over the condition that caused the patient’s injury.

Examples of Res Ipsa Loquitur Litigation

Dockswell v. Bethesda Memorial Hospital

In the case of Dockswell v. Bethesda Memorial Hospital, the plaintiff underwent a colon resection at Bethesda Memorial Hospital. After the surgery, a Jackson Pratt drain was inserted to assist postoperative drainage. Several days later, a nurse removed the drain. Unknowingly, a 4 cm piece of the end of the drain had broken off and remained inside the patient. Four months later, the patient had persistent abdominal pain and a CT showed the retained foreign body. A second surgery was required to remove the remainder of the drain. The patient then sued and sought a res ipsa loquitur jury instruction.

Because the patient already knew that the tube was inserted in his abdominal cavity and because he knew who had allegedly performed the negligent act, the trial court ruled that the res ipsa loquitur theory did not apply. The court therefore issued the jury instructions regarding the plaintiff’s duty to prove duty, breach of duty, causation, and damages. The jury ruled that there was no negligence involved in the nurse’s actions and therefore entered a verdict in favor of Bethesda Memorial.

On appeal, the Fourth District Court of Appeals agreed with the trial court, holding that a presumption of negligence was not necessary to allow the jury to resolve the issues in the case. The Florida Supreme Court agreed to review the case and reversed the trial and appellate courts.

The plain language of the Florida statute regarding medical malpractice (§ 766.102(3)(b)) states that

“discovery of the presence of a foreign body, such as a sponge, clamp, forceps, surgical needle, or other paraphernalia commonly used in surgical, examination, or diagnostic procedures, shall [cause a presumption] of negligence on the part of the health care provider.”

The Florida Supreme Court ruled that the foreign-body presumption of negligence set forth in section 766.102(3)(b) must be applied when a foreign body is found inside the patient’s body, regardless of whether direct evidence exists of negligence or who the responsible party is for the foreign body’s presence.

Because there was uncertainty how the drain fragment was actually left inside of the patient’s body and because it was clear that the drainage tube fragment was considered a foreign body under Florida law, the Supreme Court held that the trial court was required by law to issue a “presumption of negligence” (res ipsa loquitur) instruction to the jury. The Supreme Court therefore quashed the Fourth District Court of Appeals ruling and remanded the case to the trial court for a new trial that included jury instructions on the presumption of negligence due to the retained foreign body.

S.S. infant by his mother, Tricia Prisco v. New York Presbyterian Hospital

In the case of S.S. infant by his mother, Tricia Prisco v. New York Presbyterian Hospital (Nassau Co. (NY) Supreme Court No. 611750/2020), an infant underwent a liver transplant but a surgical clamp was inadvertently left inside the infant’s abdomen. The patient required a second surgery to remove the clamp. The case settled for $193,000.

Kennedy v. Abramson

Kennedy v. Abramson (100 Mass. App. Ct. 775) involved a plaintiff who was having lunch on the outdoor deck of a restaurant. When he pushed himself away from the table, a leg on his plastic chair broke and the chair collapsed, causing the Kennedy undescribed injuries. Kennedy sued, alleging negligence. The defendant restaurant could not produce personnel records or an incident report involving the occurrence. It also could not produce the broken chair or explain what happened to the chair after the incident.

The trial court dismissed the case, stating that the plaintiff had not presented any evidence that defendants were negligent and had not presented expert testimony that the chair was defective. The plaintiff had argued that res ipsa loquitur applied, allowing a jury to infer that the chair would not ordinarily have collapsed unless the defendants were negligent.

The Massachusetts Appellate Court reversed the trial court’s decision, citing Massachusetts jury instructions stating that plaintiffs may apply res ipsa loquitur if they can show that “the instrumentality causing the accident was in the sole and exclusive control and management of the defendant[,]” in addition to the accident being “of the type or kind that would not happen in the ordinary course of things unless there was negligence by the defendant.” The Appellate Court also noted that the theory of res ipsa loquitur can only be applied “if it is more likely than not that the defendant’s negligence caused the accident.” Because there were multiple issues of disputed fact, whether factors other than the defendants’ negligence more likely caused the accident, the case was reinstated and sent back to the trial court for further proceedings.

Houser v. Raef

This case involved an elderly patient who suffered a respiratory arrest in the hospital. The acute care nurse practitioner responded to a “rapid response” call. She administered sedation and paralytics in preparation for intubation. As she was intubating the patient with a GlideScope, she felt a “pop” in the patient’s neck. A subsequent CT scan of the cervical spine showed a C6-C7 fracture. The patient died 2 months later.

In the ensuing litigation, the patient’s estate argued that res ipsa loquitur applied. It claimed that the defendant was in exclusive control of the instrumentality that caused the neck fracture (the intubation setup and Glidescope) and that cervical fractures do not ordinarily occur during an intubation in the absence of negligence. The defense argued that the patient suffered from Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis (“DISH”) which made it more likely for him to suffer spinal fractures with intubation. The defense also denied using excessive force during the intubation. After a jury trial, a defense verdict was returned. In this case, the defense was able to convince the jury that although cervical fractures generally do not occur during intubation, in a patient with a rigid spine who requires emergency intubation, a cervical fracture may occur even with proper medical care.

Sample Res Ipsa Loquitur Jury Instructions

Illinois has “Pattern Jury Instructions” which instruct juries on how to determine whether a plaintiff is entitled to damages. Included within those instructions are specific instructions regarding res ipsa loquitur in medical negligence lawsuits. These instructions state the following:

The plaintiff has the burden of proving each of the following propositions:

First: That [patient’s name] was injured.

Second: That the injury [was received from] [occurred during] a [name of instrumentality or procedure] which [was] [had been] under the defendant’s [control] [management].

Third: That in the normal course of events, this injury would not have occurred if the defendant had used a reasonable standard of professional care while the [name of instrumentality or procedure] was under his [control] [management].

If you find that each of these propositions has been proved, the law permits you to infer from them that the defendant was negligent with respect to the [instrumentality or procedure] while it was under his [control] [management].

If you do draw such an inference, and if you further find that [patient’s name]’s injury was proximately caused by that negligence, your verdict should be for the plaintiff [under this Count]. On the other hand, if you find that any of these propositions has not been proved, or if you find that the defendant used a reasonable standard of professional care for the safety of [patient’s name] in his [control] [management] of the [instrumentality or procedure], or if you find that the defendant’s negligence, if any, was not a proximate cause of [patient’s name]’s injury, then your verdict should be for the defendant [under this Count].

Res Ipsa Loquitur Takeaway Points

- The theory of res ipsa loquitur applies only in narrow circumstances

- Res ipsa loquitur is an evidentiary rule that allows an injured party to introduce circumstantial evidence of negligence to prove a duty of care and a breach of that duty. In medical negligence cases, a res ipsa loquitur claim would allow a presumption that the standard of care was breached.

- Even if a res ipsa loquitur claim is raised, a health care provider can overcome the presumption of negligence by providing plausible explanations or other reasonable evidence showing why negligence did not occur.

Need help with tricky medicolegal concepts? I give lectures on medicolegal terms like this that are often seen on medical board exams. Contact me and I can try to help you.